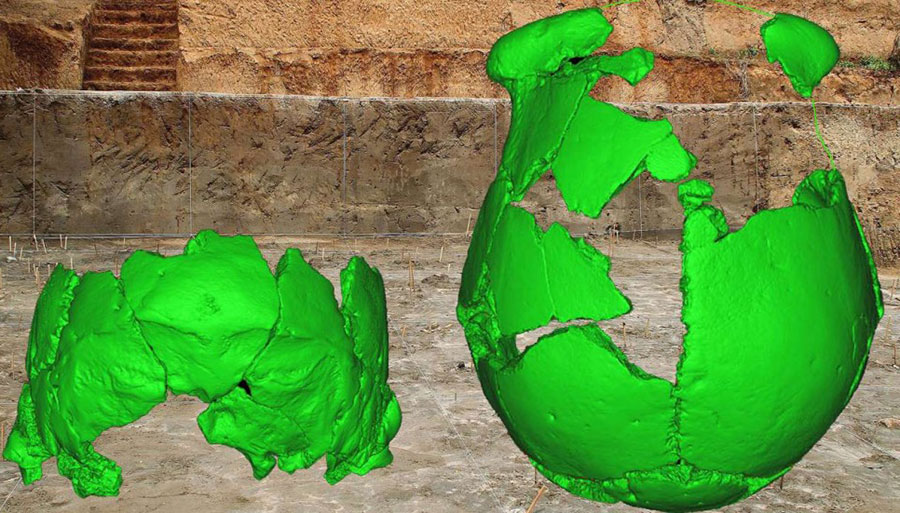

Researchers analyzed two skulls recovered from central China dated back 100,000 to 130,000 years ago and discovered features native to Eurasian humans alongside others that are closer to those of Neanderthals.

The discovery shows that there are still undiscovered trends in the evolutionary adaptation of humans, mainly because of the lack of well-preserved human remains in eastern Asia.

The theory is that the Homo sapiens or modern human displaced other genera of hominids as they encountered them. Within these displaced populations lie Denisovans and Neanderthals. Furthermore, it is known that these populations interbred at some point in history.

“There’s a certain amount of regional diversity at this time, but also there are trends in basic biology that are shared by everybody. And the supposed Neanderthal characteristics show that all these populations were interconnected,” stated Erik Trinkaus, from Washington University to BBC News.

More clues about the link between Neanderthals and Homo sapiens

Trinkaus commented that some features presented by the skulls were notably more pronounced in earlier humans. For example, the bones behind the eyebrows and a prominent skull backside were much less “archaic” in the two skulls than in older specimens. Apparently, this is due to a process where bone mass is lost as a species evolves, a trait shared by other hominid species.

Another interesting feature is that the specimen whose skull was named Xuchang 1 seemed to have a large brain, comparable to the largest Neanderthal brain held on a record. Sadly, the skulls could not be compared to the Denisovans because they were not fully preserved, as they lacked everything on their face that’s below their eyebrows.

Looking for the elusive Denisovan

Researchers know that Denisovans split from Neanderthals about 400,000 years ago, according to remains found in Atapuerca, Spain. This suggests that they most likely present Neanderthal features altered by the evolutionary process. Currently, they are looking for additional DNA samples to determine if the skulls enter in the Denisovan lineage or are a wholly different kind of hominid.

The first remains of a Denisovan were discovered in Siberia in the form of a tooth and a finger bone. DNA tests of the finger bone revealed that its genetic structure was different to that of Neanderthals and modern humans, although other studies then suggested that Denisovans shared a common ancestry with Neanderthals. In fact, at least 3 percent of Aboriginal Australians have Denisovan DNA.

Their name comes from the place where the discovery took place, Denisova Cave, in the Altai Mountains in Siberia, bordering China and Mongolia. The cave took its name from Denis, a Russian hermit that inhabited the location in the 18th century.

In that same cave, researchers found a stone bracelet that dated back 40,000 years. It was made of polished green stone (chlorite) and is theorized to have adorned a “very important woman or child on only special occasions,” according to Siberian Times. Reportedly, the bracelet reflects sun rays and casts a green shadow at night by the fire.

“The ancient master was skilled in techniques previously considered not characteristic for the Palaeolithic era, such as drilling with an implement, boring tool type rasp, grinding and polishing with a leather and skins of varying degrees of tanning,” wrote the researchers responsible for analyzing the bracelet.

It is not yet clear whether the bracelet belonged to a Denisovan or to a modern human.

Source: Science