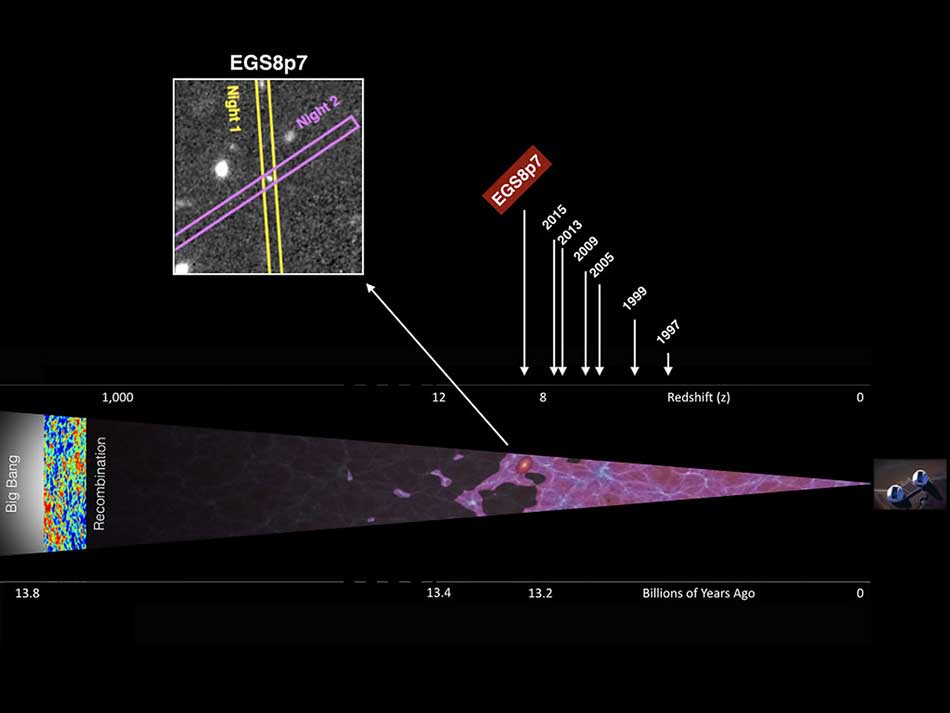

California – A group of astronomers from the Californian Institute of Technology (Caltech) detected what may be the farthest galaxy ever found. An article published in the Astrophysical Journal Letters, shows data for the galaxy, labeled as EGS8p7, that is beyond 13.2 billion years old, while the universe itself is around 13.8 billion years old.

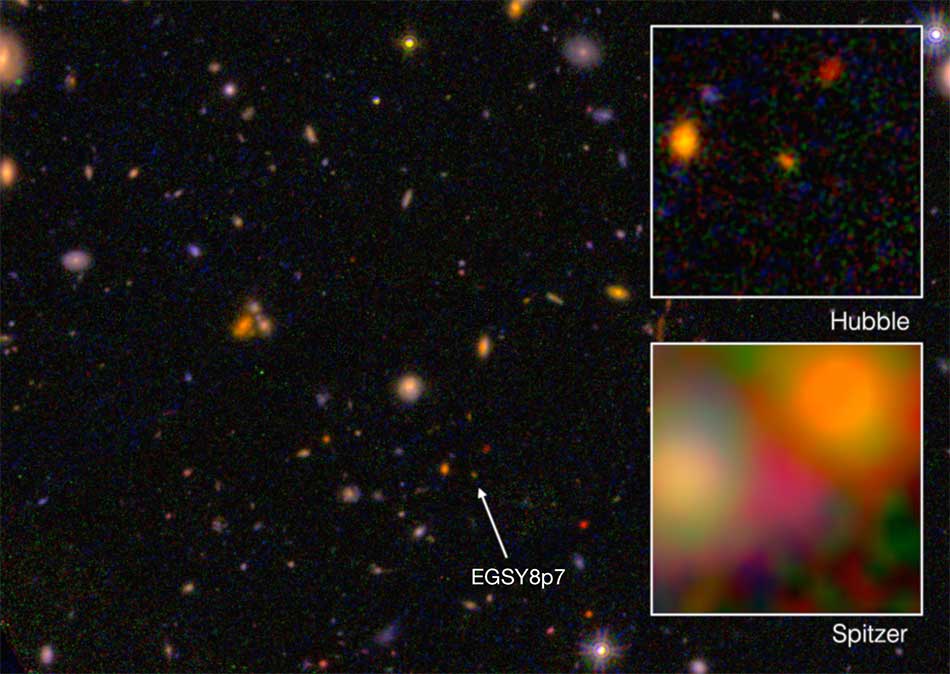

This galaxy called for the attention of the researchers earlier this year when telescopes such as The Spitzer Space Telescope (SST) – an Infrared Telescope – and the Hubble Telescope – which is one of the largest and most versatile tool for astronomers – accumulate enchanting data that prompted that EGS8p7 may be the earliest galaxy ever found since the beginning of the universe. So, the celestial object was chosen for further investigation.

Credit: Adi Zitrin/ Caltech.

Spectrographic Analysis

To pursue the research, the Caltech team used a multi-object spectrometer for infrared exploration (MOSFIRE) at the W.M. Keck Observatory in Hawaii, performing a spectrographic analysis.

They aimed to define the redshift from the new celestial object. The redshift is the displacement of spectral lines toward the end of the spectrum which is called ‘wavelengths’ and its traditionally used to quantity the distance to galaxies. The astronomers explained that just after the Big Bang, the universe was sort of a soup of charged particles, electrons, protons and photons – or light, as we know.

“Because these photons were scattered by free electrons, the early universe could not transmit light. By 380,000 years after the Big Bang, the universe had cooled enough for free electrons and protons to combine into neutral hydrogen atoms that filled the universe, allowing light to travel through the cosmos. Then, when the universe was just a half-billion to a billion years old, the first galaxies turned on and reionized the neutral gas. The universe remains ionized today,” the press release from the Caltech, reports.

Furthermore, researchers explained that clouds of neutral hydrogen atoms would have absorbed a relevant quantity of radiation discharge by the earliest galaxies ever formed. Thus, this included the Lyman-alpha line, which is in the ultraviolet portion of the electromagnetic spectrum. That means that at least in theory it shouldn’t be possible to observe a Lyman-alpha line from the EGS8p7. But instead, they find Lyman-alpha emissions from the celestial object, which implicate tracers of cosmic reionization.

Credit: I. Labbé (Leiden University), NASA/ESA/JPL-Caltech

“If you look at the galaxies in the early universe, there is a lot of neutral hydrogen that is not transparent to this emission. We expect that most of the radiation from this galaxy would be absorbed by the hydrogen in the intervening space. Yet still we see Lyman-alpha from this galaxy.” said Adi Zitrin.

Astronomers ensure that further spectroscopic follow up of such bright sources are currently promising important insights into the early formation of galaxies. The more we get to know our past and how did it molded, the more we understand our current situation.

Source: CALTECH

So the reason we can see it is because it’s a from such an ancient time?