China’s Tiangong 1 is expected to crash anywhere on Earth between October and April 2018, as China has told the United Nations. Although much of the 8½-ton laboratory will burn up in the atmosphere during its reentry, debris weighing up to 100kg could hit the surface. It is impossible to tell where these pieces will fall.

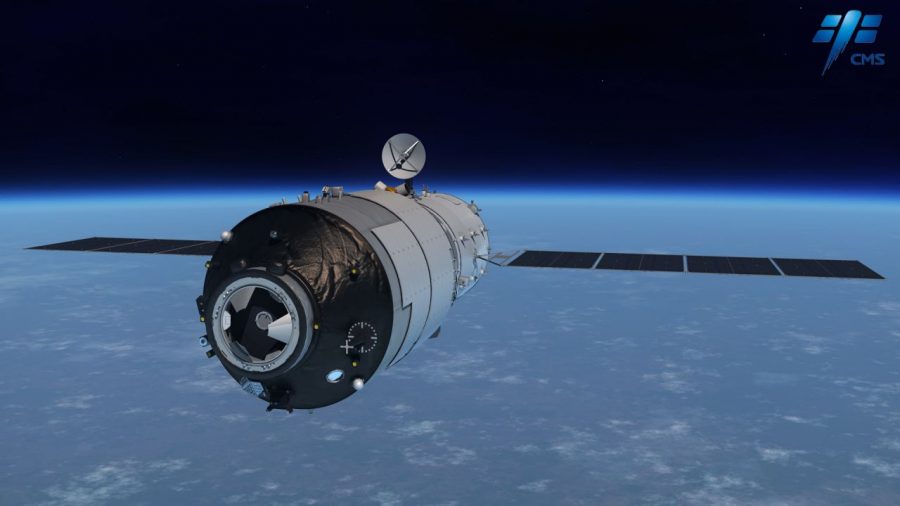

Launched in September 2011, Tiangong 1 is a prototype for a permanently manned space station the Chinese want to build and launch by 2020 but they confirmed they had lost control of the spacecraft six years after it went into orbit.

The protocol for spacecraft that remain in control consists of guiding their reentry to the Oceanic Pole of Inaccessibility. Between 1971 and June 2016, more than 263 spacecraft had landed at the 2.5-mile-deep “spacecraft cemetery”, located about 3,000 miles off the eastern coast of New Zealand and 2,000 miles north of Antarctica.

Tiangong 1 translates to “Heavenly Palace” and it is China’s first space laboratory. It ended its mission in March after having served as a base for space experiments for two years longer than planned. China’s first female astronaut, Liu Yang, made history in 2012 as part of two three-person crews on the station.

Since its service ended, the spacecraft has been falling gradually but it started to descend faster a few weeks ago. Jonathan McDowell, a renowned astrophysicist from Harvard University, told the Guardian that the laboratory’s perigee was below 300km and is already in the denser atmosphere.

China’s Heavenly Palace, which measures 34 feet in length, could crash on any continent depending on changes in atmospheric conditions, McDowell explained.

“Even a couple of days before it reenters, we probably won’t know better than six or seven hours, plus or minus, when it’s going to come down. Not knowing when it’s going to come down translates as not knowing where it’s going to come down,” McDowell was quoted as saying by The Guardian.

In May, China told the United Nations’ Committee on the Peaceful Uses of Outer Space that the chance that the crashing craft will harm people or damage aviation and ground activities is remote. However, authorities said they would closely track the station’s descent and keep the UN informed.

Not the first out-of-control spacecraft crash

Many other larger spacecraft have reentered the planet without human control and none have caused injuries to people.

Some large debris landed outside Perth in Western Australia in 1979 after Nasa’s 77-tonne Skylab space station crashed to Earth. And in 1991, The Soviet Union’s 20-tonne Salyut 7 space station crashed to our planet while still docked to Cosmos 1686, another spacecraft. They scattered debris over a town in Argentina.

Tiangong 1’s launch in 2011 was considered an important political symbol and a geopolitically relevant event as part of China’s broader space program. In September 2016, the Asian country launched its second space laboratory, Tiangong 2, which will replace the first experimental station.

A space station of its own is China’s only alternative

China’s efforts to build its own orbiting laboratory have increased given that the country’s experts are not allowed on the International Space Station (ISS). Known as the Wolf amendment, a U.S. law prohibits NASA to team up with Chinese government entities due to national security concerns.

The United States fears that the Chinese would take its intellectual property, as well as its national secrets and treasure, as space analyst Miles O’Brien told CNN in 2015.

It is highly unlikely that resistance from U.S. legislators will continue banning the Chinese presence on the ISS but an experiment by the Asian country recently arrived at the orbiting lab. A Chinese DNA research reached the ISS last June aboard a SpaceX Dragon cargo spacecraft.

NanoRacks, a Houston-based firm dedicated to helping other companies and institutions make use of the outer-space laboratory, teamed up with the Beijing Institute of Technology to fly China’s first commercial payload to the ISS.

The researchers want to find out whether space radiation and microgravity cause mutations among antibody-encoding genes, according to Xinhua news agency. The experiment was installed in the U.S. area, where astronauts have conducted studies and sent data to the Chinese researchers on Earth.

The state-run news agency informed that the DNA experiment is “purely commercial” and does not violate the Wolf amendment.

“This cooperation does not violate any laws and regulations, including the Wolf amendment. We do it in an open and visible way,” Deng Yuling, lead author of the Chinese research, told Xinhua. “This is a new model of cooperation that we can follow in the future.”

Chinese space missions

China was able to launch its first manned space program in 1992 through the use of Russian technology, which allowed the nation to put the first Chinese man in space in 2003.

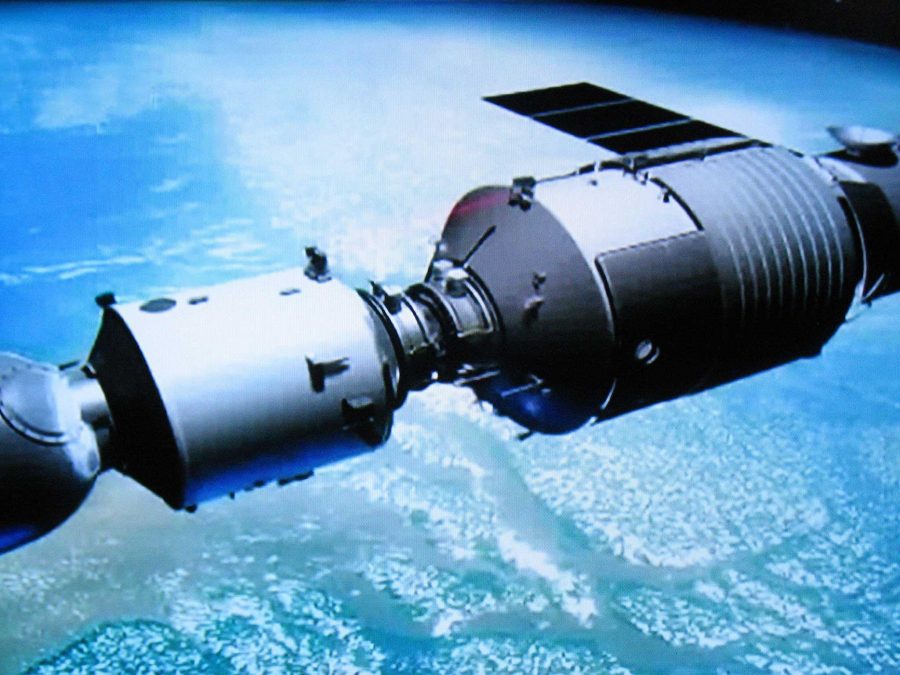

The Shenzhou, a Chinese spacecraft very similar to Russia’s Soyuz, completed the country’s longest space mission to date the same year after docking twice at the now out-of-control Tiangong 1. China’s first spacewalk was completed later in 2008 and its first successful unmanned space mission to orbit the moon and back in October 2014.

Source: The Guardian