Deep-water scientists have discovered yet another species of yeti crabs known as Kiwa tyleri more than 8,500 feet or 2,600 meters deep in the hydrothermal vents off East Scotia Ridge in the Antarctica, and scientists find its features and lifestyle very fascinating.

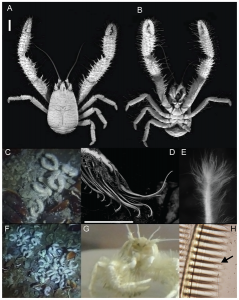

The hairy and white crab is about 15 centimeters to 0.5 centimeters in length, and lives close together in a tight community close to the super hot hydrothermal vents in the bottom of the ocean. It has short and robust from limbs, and looks stout and compact with the ability to climb much more easily.

According to Sven Thatje, the study leader and an ecologist from the University of Southampton in the UK, the moment they discovered the yeti crab Kiwa tyleri they knew something was up.

They pack themselves close together – with about 700 specimens filling about 11 square feet of space – meaning they even pack themselves on top of one another, very close to the super hot vent spewing forth hot water that is over 700 degrees Fahrenheit or about 400 degrees Celsius.

The researchers found out that while the Kiwa tyleri cannot live within the vents because they are exceedingly hot, they still cannot live too far away from it because the waters of the Antarctica is exceedingly cold with a tendency to freeze; meaning they have to pack themselves together close to the vents.

The marine scientists who noted that female Kiwa tyleri with eggs could move away a little bit to warmer areas that is not too hot or too cold to release her eggs to hatch, because the yeti crab larvae would not survive the hot hydrothermal vents temperature not cold freezing areas.

Given that female yeti crabs have to move out into colder parts away from the super hot vents to release her eggs, the cold region affects her body and drains her energy so much – meaning that it is possible they only breed once in their lifetime before dying.

And one more thing about the yeti crab Kiwa tyleri – it was named after emeritus professor Paul Tyler of the University of Southampton and a pioneer in deep-sea research.

Source: Plos.org.