Sheriff Richard Jones from Butler County, Ohio –where drug overdose is the leading cause of death- said he won’t equip his deputies with naloxone, an opioid overdose reversal drug that saves many lives around the United States every day.

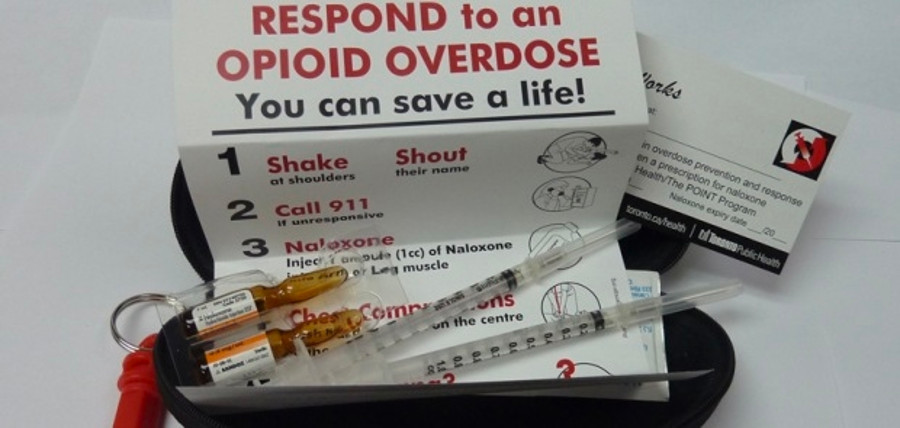

Jones stated that his officers don’t carry Narcan –a brand name of naloxone- nor will they. The drug is typically administered nasally and works by binding to parts of the brain affected by dopamine during an overdose, blocking the effects of the narcotics or opioids for 30 to 90 minutes and giving the body back its respiratory ability.

The sheriff reassured his position against naloxone citing high costs and concerns about their officers’ safety, saying that some overdose victims revived with the reversal drug can be unpredictable and hostile. He recently told Ashleigh Banfield on HLN’s “Primetime Justice” that the only way to change his position would be “if the courts order” him to give naloxone to his deputies.

Sheriff Jones believes overdose reversal drugs just enable addicts to continue consuming opioids

Jones, a public supporter of President Donald Trump, is known for his anti-drug views. He stated that he’s gotten positive responses from his remarks because people are, too, “disgusted by the drug problem.”

“This Narcan, all it does is save people’s lives for another day,” said Jones, according to The HuffPost. “You enable these people when you give them this Narcan.”

The sheriff doesn’t believe addiction is a disease, even though experts have said it is. He noted an increase in the number of young women giving birth to opioid-addicted babies in jail and that he’s heard far too many stories about young children being directly affected by opioid addiction.

Jones explained that while his officers won’t carry naloxone, overdose victims will still be revived.

“The life squads aren’t just going to stop giving them Narcan, but it’s pushing the resources out so bad and our government has no response, they have no cure, they’re all too busy,” Jones said. “Nancy Reagan, as silly as it might sound, you gotta just say no and you gotta teach kids and you gotta start in the 7th grade.”

Middletown councilman suggested denying naloxone to people who’ve been revived twice

Butler County saw almost 200 drug overdose deaths last year. More than 150 of those deaths were attributed to heroin or fentanyl. Fentanyl is a potent synthetic opioid that has helped fuel drug deaths around the country. According to The New York Times, the county is on its way to see 263 overdose deaths this year. Its neighbor, Montgomery County, will see over 800 drug overdose deaths this year if they continue at the current rate.

The opioid epidemic has spurred different views and opinions on how best to respond. In June, a city councilman in Middletown –located in both Butler and Warren counties- asked deputies to analyze denying emergency medical services to people who had sought a medical intervention at least twice before.

Councilman Dan Picard said that people shouldn’t want to come to Middletown to overdose because someone might not come with Narcan and save their lives. Picard said they need to put a fear about overdosing in Middletown.

He cited mounting cost of overdose reversal kits and noted the city is spending almost ten times the amount it had initially budgeted for Narcan in 2017. Middletown officials said that they’d continue reviving any overdosed person they encountered.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention say that naloxone has saved over 26,000 lives between 1996 and 2014. Experts say that an overdose reversal drug kit costs $37.50

Drug policy advocates say the police won’t solve the epidemic

Drug policy advocates believe that some officials’ –like Jones- views aren’t representative of most officials who are in charge of dealing with the opioid crisis.

“We see a lot of consistency and buy-in from law enforcement, fire and EMS on the importance of overdose response and harm reduction, and the importance of an enhanced overdose response,” said Kelly Firesheets, senior program officer at Interact for Health in Cincinnati. “A lot of times we get confused and forget that naloxone is not treatment for addiction.”

Firesheets shared concerns that Jones’ remarks would limit the department’s ability to protect deputies who may come into contact with synthetic opioids, some of which are so lethal that can be deadly to the touch. She believes the sheriff’s views are clear evidence of the lasting stigma around drug addiction.

Michael Collins, the Deputy Director of the Drug Policy Alliance, said police won’t solve the overdose epidemic, and that there needs to be a public health approach to solve it. An approach based on science, health and human rights, and not enforcement, he added.

Naloxone doesn’t prevent addicts from relapsing, and some people fear that its availability, combined with the availability of cheap narcotics and opioids on the streets, fuel drug abuse. Vermont State Police captain Rick Hopkins told the Marshall Project that it’s a matter of perspective: you can either look at naloxone as an enabler or you can look it as you’re helping fellow human beings survive until they get healthy.

Source: HuffPost