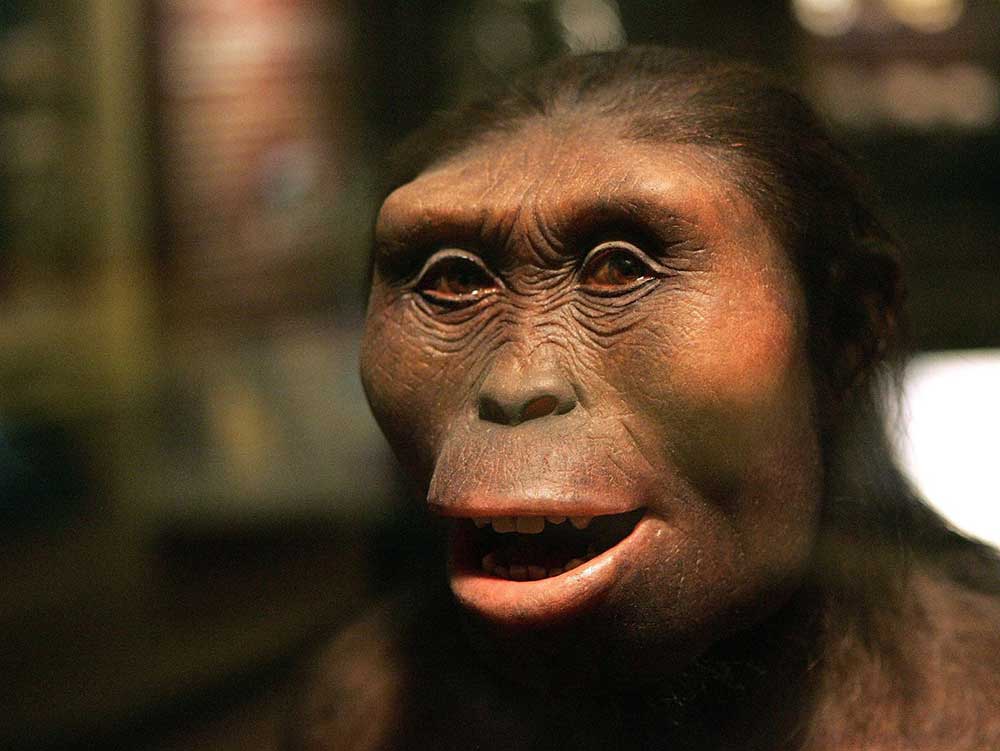

California – The University of California, San Francisco (UCSF) released a new study that suggest relevant evidence about the real evolution of humans and its previous ancestors. According to this new research, the ancestor of modern humans may look more like a chimp or a gorilla, based on the shoulders.

The study was titled “Fossil Hominin Shoulders Support and African Ape-like Last Common Ancestor of Chimpanzees and Humans” and it was published in the journal PNAS. “Our study suggests that the simplest explanation, that the ancestor looked a lot like a chimp or gorilla, is the right one, at least in the shoulder.” Said Nathan Young, PhD, assistant professor at UC San Francisco School of Medicine and lead author of the study.

The Last Common Ancestor

It’s been nearly 7 millions years since the humankind took different paths separate from African apes who were believed to be our closest relatives. However, over time, experts have noticed that human traits are more similar to distantly related orangutans or even monkeys. This combination of certain characteristics, cast doubt on the real appearance of the last common ancestors of modern humans and African apes. The study suggest that the ancestor looked more like a modern day chimp and a gorilla, even ancient apes, unlike any other living group.

“Humans are unique in many ways. We have features that clearly link us with African apes, but we also have features that appear more primitive, leading to uncertainty about what our common ancestor looked like.” said Young.

PHOTOGRAPH BY DAVE EINSEL, GETTY IMAGES

Professor Nathan explained that, it is the shoulder shape that demonstrates the changes in early human behaviors, such as climbing and tool use. Furthermore, the shoulders of African apes are shaped as a “trowel-shaped blade and a handle-like spine” that suggest, the joint with the arm up pointing to the skull, this characteristic gives a dominance to the arms when swinging through the branches or common climbing, as we know.

On the other side, the scapular spine of monkeys is pointed more to the bottom. Regarding to humans, this trait is even more alike and pronounced, it indicates behaviors like stone tool making and also high speed throwing. Previously, it was questioned if humans develop this arrangement from an earliest ape, or from a modern African-ape-like creature. But the bottom angle was reverted back.

Testing…

In order to determinate this suggestions, researchers tested different fossil shoulder blades of early hominins and modern humans against African apes, orangutan, gibbons and large, tree-dwelling monkeys. Results showed that modern human’s shoulder is unique in that it shares the lateral orientation with orangutans and the scapular blade shape with African apes; a primate in the middle.

Nather Young claimed that shoulder blades were strange, distinct from all the apes. Gathering characteristics such as primitive, derived in other ways but different from all of them.

The team of researchers from the UC of San Francisco, raised certain questions such as how was the evolution of humans, and where did the common ancestor to modern humans evolve a shoulder like ours. To answers this inquiries, both early humans -Australopithecus species- and the primitive -A. afarensis-, -A.sediba- and H.ergaster.- were analyzed in order to find out if they fit on the shoulder spectrum.

Findings

According to the data provided by the analysis, – Australopiths, were intermediate between African apes and humans.- and -The A. afarensis looked more like an African ape than a human shoulder- and finally, A. sediba shoulder was more likely to humans than to apes.

“The mix of ape and human features observed in A. afarensis’ shoulder support the notion that, while bipedal, the species engaged in tree climbing and wielded stone tools. This is a primate clearly on its way to becoming human.” said Zeray Alemseged, PhD, senior curator of Anthropology at the California Academy of Sciences.

Researchers highlight the importance of this shoulder’s transformation, due to its link to our ability of throwing objects with speed and accuracy. This facility of high-speed throwing is a unique behavior of humans and it’s because our facing blade allow us to store energy in our shoulders. “Our unique throwing ability likely helped our ancestors hunt and protect themselves, turning our species into the most dominant predators on earth.” stated Neil Roach, a fellow of human evolutionary biology at Harvard University.

Next step

UCSF team will go further with this study aiming to find out why nowadays humans tend to develop shoulder injuries, and in spite of that they still possess their high speed characteristic; Researchers want to find out the variations on the shoulder of every human so they can prognosticate which humans are at higher risk of suffering from an injury, just before it happens.

“Once we understand how the shape of the shoulder blade affects who gets injured, the next step is to find out what genes contribute to those injury prone shapes. With that information, we hope that one day doctors can diagnose and help prevent shoulder injuries years before they happen, simply by rubbing a cotton swab on a patient’s cheek to collect their DNA”. Terence Capellini, PhD, assistant professor of human evolutionary biology at Harvard University, concluded.

Source: PNAS